An Uncommon Level of Common Sense

Jim Carey spent the first part of his life unsure of his path; he’s spent the second at a full sprint.

Swarthout was trying to figure out what had happened. It was April 20, 2008. One moment he’d been riding his motorcycle and the next he was in the trauma unit at Regions Hospital. Doctors were talking about amputating his left leg below the knee. What was going on?

Traffic had been heavy that day, and many vehicles were right up against the line. One guy with three golf-course beers in him just happened to go over it. Swarthout mainly remembers flying through the air.

Now, a decision had to be made about his leg. Swarthout and his wife authorized the amputation. Swarthout’s wife did one more thing: she called Jim Carey. By August, Swarthout had a seven-figure settlement.

Plenty of attorneys have the law in their blood. But with Carey, one gets a sense he might actually test ABA positive.

The Carey name goes way back in Minnesota, particularly on the Iron Range. Carey’s great-grandfather, after whom he’s named, was a judge in the city of Virginia from early in the century until 1946. Carey’s father, Thomas, practiced insurance defense on the Range before becoming a judge in Hennepin County. His uncle John ran a small firm in Fairfax before coming to SiebenCarey.

He grew up in the union brotherhood; his friends were the children of steelworkers. He played sports and went to Catholic mass with them, and figured his life might be similar to theirs. A law career wasn’t on his mind. The military perhaps, like his uncle John, who served in the Marine Corps before becoming a lawyer. He wasn’t sure. He just knew he didn’t like school that much.

But he enrolled at St. John’s University in Collegeville anyway. It was a good four years. He did well and made a lot of friends, yet career inspiration still hadn’t struck. People kept telling him to go to law school. He wasn’t sold on anything other than marrying his high school sweetheart, Molly, and starting a family.

Which meant he needed a job. And that’s when being a Carey proved to have advantages even outside of the Iron Range. His father called his old courtroom adversary Harry Sieben, a personal injury lawyer with his own firm who also happened to be the speaker of the state House of Representatives.

“Tom asked if I would talk to him,” says Sieben, 71, of that conversation in 1982. “I liked Jim. I put him in a research position for the DFL caucus, and he did a very good job. He was really good at boiling down complex issues for people, which is a lot of what he does today.”

Politics would have been a good fit for Carey. He had the gifts: a warm demeanor, a social personality, a Clinton-like gift for making other people feel important. But it was working with Sieben in politics that finally convinced him that he wanted to work in the law.

“I guess I needed to try some other things first,” says Carey from his office in downtown Minneapolis. “Once I started at William Mitchell, I knew it was the right decision. It was the first time in my life I actually enjoyed schoolwork.”

He and his wife lived in a duplex a couple blocks from the law school in a not-great neighborhood. The property owner and resident of the other unit was a biker, and he often had five or six buddies over. There constantly were Harleys parked out front, for which Carey was grateful. He always knew Molly was safe when he was away buried in books.

While in law school Carey clerked for Sieben at what was then Sieben, Grose and Von Holtum. “I knew I wanted to be a trial lawyer and represent individuals, not banks or insurance companies. My time with Harry only confirmed that,” he says.

When he graduated in 1987, a job was waiting for him. And that’s when Carey learned something about himself: he had a lot of ambition. He wanted responsibility. And he wanted to push himself. When an opportunity came up, he seized it.

“We had a farm accident case where the plaintiff had brain damage. The case came to trial and I wasn’t available to do it,” Sieben says. “Jim wanted to do it. I cleared it with the client and Jim did a great job with it.”

He also soon nabbed his first million-dollar jury verdict, which raised eyebrows around town. “A verdict of that size back then was pretty rare,” Sieben says.

The rest of his career has unfolded like a William Mitchell recruiting brochure. Big cases, big recoveries, big reputation. He had the name of a movie star and a legal career to match. City life suited him, but he never stepped too far from his union brothers and sisters on the Range.

“I don’t mean to sound melodramatic, but I’m really proud that I can go back up and can help the people that I grew up with,” Carey says. “I work a lot with plumbers and pipe-fitters and carpenters. I know these people.”

What he has is common sense. Carey should have it on his card right next to “know your rights.” It comes up in almost any conversation about him. Proof:

“I believe in common sense and that’s what Jim has,” says client Swarthout.

“Jim always leads with a warm smile and a firm handshake and follows up with a common-sense argument that a jury can understand,” says Jim Schwebel of rival personal injury firm Schwebel, Goetz & Sieben.

“He has an uncommon level of common sense,” says Sieben.

But Carey’s success comes from more than that, says Schwebel. “It’s about Jim’s integrity. One of the best proofs of that is that on many occasions he’s been selected by both plaintiffs and defense counsel to serve as the sole arbitrator to resolve a case. That’s rare,” he says.

The courtroom can be a macho, adversarial place. Carey can fight, but he can also show compassion.

“Most lawyers have a hard time expressing their feelings about these things, but not Jim,” says Sieben.

He’s realistic about how much what he does helps clients. “You’re talking about exchanging money for someone’s loved one,” Carey says. “It isn’t equal. If you think it is, you don’t have a heart. We can help people get their life back on track with compensation but that only goes so far. It’s hard.”

Some lives do turn around. Take Swarthout. He is thriving again, thanks to ongoing physical therapy and smart management of his settlement money. He and his wife thank Carey. “I used to think lawyers were all the same until I met Jim,” he says. “He made me eat my words.”

Not every case works out. Take the case of Kevin Harms. “That’s one that still keeps me up,” Carey says.

Harms was a patient in a psychiatric ward at Mayo Clinic when he went out for a walk one night in 2009 and jumped to his death from a parking ramp. Carey sued for negligence. It was a civil case against Mayo tried in Rochester—tough to win. And he didn’t; Mayo was cleared of liability. But Carey still thinks about it.

His opinion? “This was a relatively young guy going through a bad bout of depression and was let out of a secure ward when he shouldn’t have been,” he says. “It sticks in my craw because we should have won. It’s the one case in my mind where I think about some of my choices. Maybe if I had done this a little different, the outcome would have been different. That’s a hard one for me to let go.”

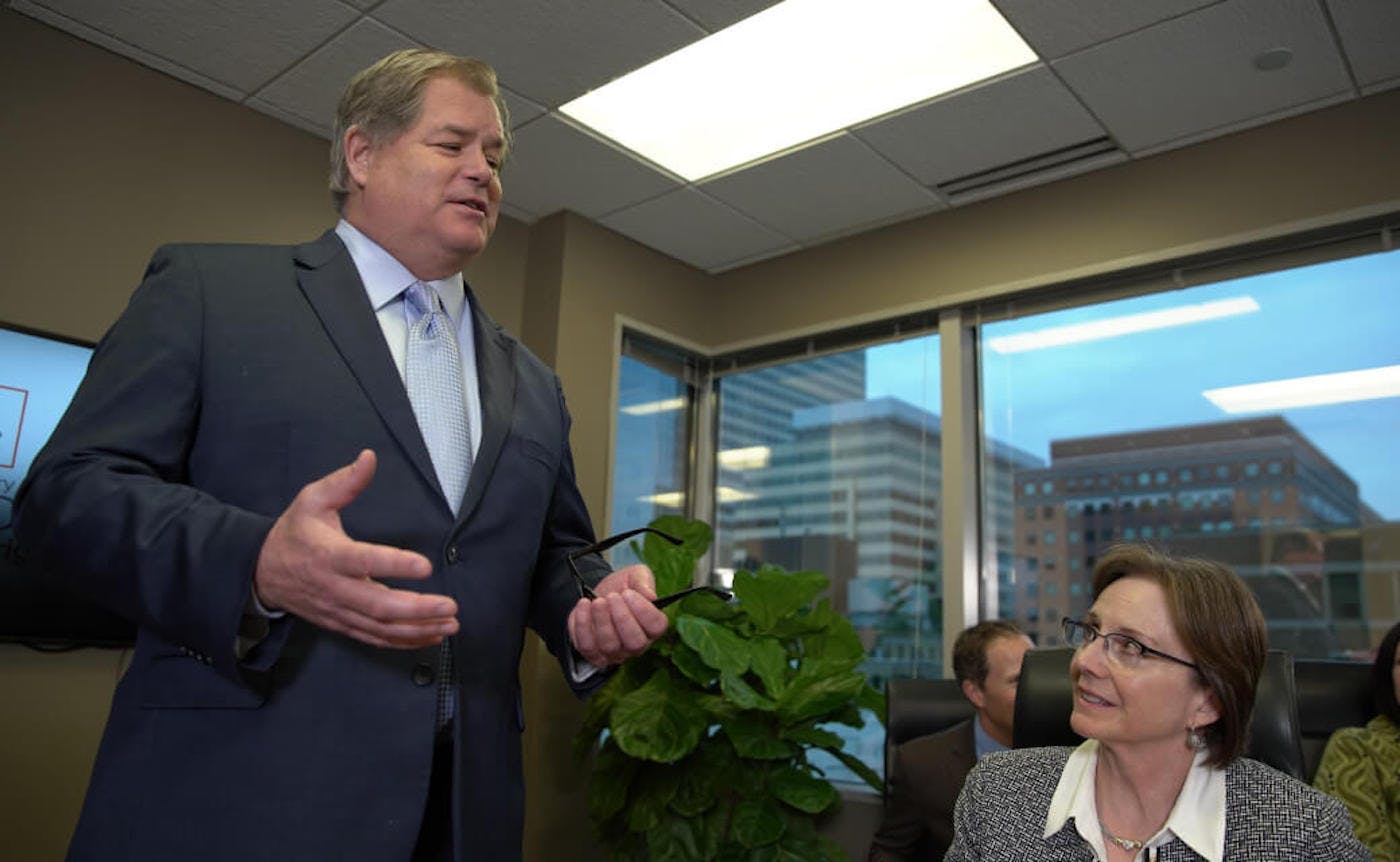

Carey is 55 and has three kids out of the house. He has the look of a contented, proud family man—and the look of a TV or movie dad.

Ten years ago, Carey and his wife packed up their Edina house and moved into a secluded area in Forest Lake, which reminds him of his childhood. “It’s beautiful,” he says. “We don’t have any close neighbors, probably a quarter mile away, and we have wildlife, solitude, quiet. We have our 40 acres.”

Even though he’s now the managing partner of the firm, a position granted him four years ago in a decision Sieben says was unanimous among the partners, he still carries a heavy caseload. Carey has between 80 to 120 files he’s working on, and a whiteboard in his office with 14 cases being prepped for trial. He works like he’s making up for lost time.